For many people, the Internet has become an irreplacable part of both work and entertainment. Whether we’re sending an email to our boss, marathon watching series on Netflix, doing research, shopping on Amazon, managing our online bank accounts, or just idling on Facebook, the fun part and the work part often run very closely alongside each other.

It has almost become a cliché to complain about procrastination caused by the Internet. It’s like a giant hall of mirrors, reflecting us back to ourselves in a myriad different ways: one moment we’re leaving an angry comment on a YouTube video, the next we’re sharing inspirational platitudes on Social Media. The Internet is like a neverending roadside show of baby animals, amateur acrobats, live concerts and high school reunions.

And it all begs the question: How the hell are we going to get any work done in this place?

Fuzziness of Attention

In a world of instant notifications, sounds and popup windows, our attention is in a constant state of disruption. As Linda Stone once said, we are suffering from “constant partial attention”. In other words, we’re never fully paying attention, part of us is always wrapped up in that advertising flashing in our peripheral vision, that email notification sound, the little red numbers accumulating on our Social Media apps.

Multitasking has been our instinctive response, but it’s less of a coping strategy and more of a desperate measure, because it creates a lot of stress and often doesn’t bear any fruit — as the old saying goes: “hunt many rabbits, catch none”

The Assembly Line Model Of Work

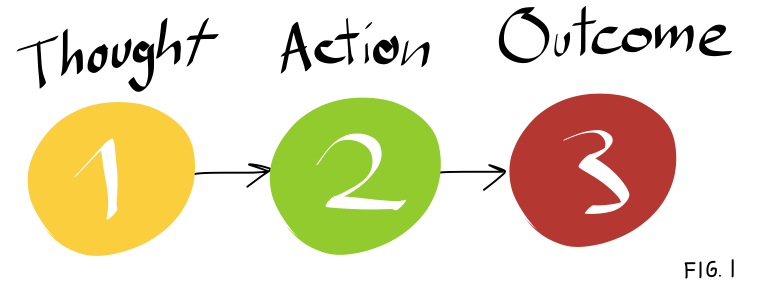

In the assembly line model of work (Fig. 1), there are three distinctive steps or stages, connected in a linear way. First, there is an idea, then there’s the action or applicaton and at the end there’s the outcome.

This chain works very well, as long as there are no distractions, no phone calls, instant messages, tempting funny videos just a click away and so on and so forth.

The only way to still follow this chain in an always-online word is with strict discipline. That means, disabling all popups, notifications, putting your phone on mute and removing any potential distractions.

It’s still a valid strategy and “Digital Discipline” or “Attention Hygiene” should be an essential part of high school curriculums worldwide.

However, we should also be aware that we’re applying an outdated model to a changed landscape. The Internet is not a perilous territory against which we have to protect ourselves by all means, guarding our attention and clarity of mind like a ninja in the night.

And maybe we can’t change the way the world works, but we can certainly change the way we work with it.

From Assembly Lines to Hyperlinks

Each tiny piece of data on the Internet is linked to a million others, not in a linear fashion, but more like a web.

Everyone of us has experienced the phenomenon of going to Wikipedia about a certain topic of interest, clicking a Hyperlink, another one, and another one until we barely remember what it was we started with.

Associative Thinking

Associative thinking is defined as “an unconscious or uncontrolled cognitive activity in which the mind wanders.”

In a way, this describes the way we behave online. When we let our digital guard down, we tend to wander aimlessly from one webpage to the next, bobbing along the waves of our newsfeeds, lazily scrolling through comment-sections and related posts until we find something that tickles our fancy.

Instead of fighting this kind of behavior as “unproductive” or incompatible with the assembly line model of work, maybe we could embrace it and integrate it with the way we operate online?

Associative Doing

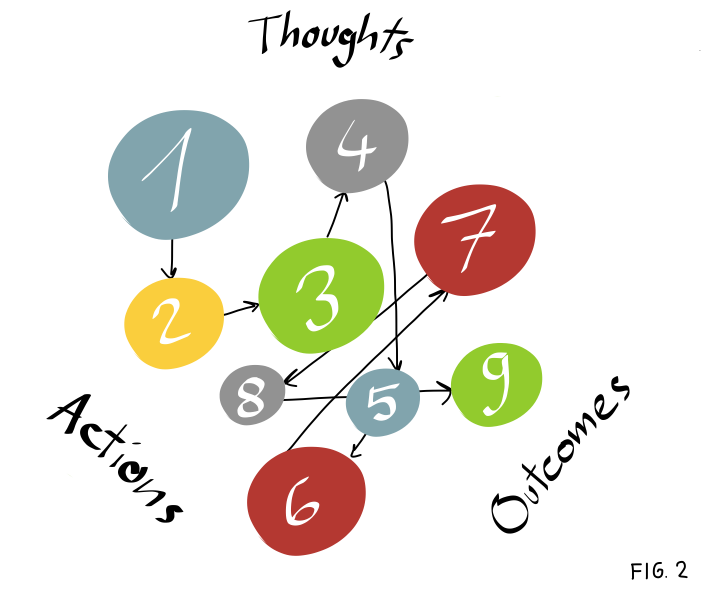

In this new model of work (Fig. 2) which I’d like to call “associative doing” we’re not just aimlessly drifting. We’re still following a course, but we’re also open to opportunity. Instead of only one thought, one action, one outcome, there are always multiple thoughts, actions and outcomes.

Associative thinking is often linked to creativity because it’s like day-dreaming. It’s in that semi-aware state that humanity’s greatest discoveries were made. It’s when we stop controlling our attention too much that we often stumble upon simple or elegant solutions we never would have thought about.

Associative doing implies the application of associative thinking to our course of action in a hyperlinked world.

We might start with the thought of writing an article, but during our preliminary research we find something, share it on Social Media, and a friend comments about it. We exchange a few messages, the friend sends you a link, and through this link you’ll find another link which completely changes your initial thought or thesis. From this renewed discovery we might end up with a significantly changed outcome or even start a new chain of work.

Adjusting Our Focal Length

In the assembly-line model we do one thing after the other, often with great efficency and productivity but our attention becomes over-focused and we miss out on unplanned discoveries (serendipity).

In the multitasking approach we try do everything at once and don’t get anything done.

As noted before, sometimes it’s just best to put on blinders and power through without noticing anything else.

In the “associative doing” model, however, we follow a loose course but we don’t close off our peripheral vision.

We don’t do one thing after the other or everything at once but everything at its time.

How to distinguish when to block of or to welcome a “distracting” factor is impossible to formalize. It might just be a matter of being in the moment and working it out as one goes along …

–