The word “samurai” evolved from the word “saburai,” which itself is rooted in the verb “saburau,” meaning “to serve.” The kanji for samurai, 侍, is composed of two components, or “radicals”: a man (on the left), and a temple (on the right). Thus, just as a man pays homage to the kami (spirits/ gods) at a temple, the samurai pays homage to his lord.

Originally, the samurai (though they were called saburai until the 16th and 17th centuries) were the lowest six of twelve classes of retainers of the Emperor of Japan, back when the Emperor was still the last word in secular authority. Thus, the samurai were roughly equal to civil servants, save for the fact that they owed their loyalty to the Emperor personally, not an abstract system of government. Japan, having clashed with the Tang Dynasty of China, sought to adopt Chinese governmental structure and philosophy to support a more efficient and effective military. This meant adopting the Confucian idea of serving one lord, rather than “the people” as an abstract force.

At the time, this lord was the Emperor himself.

In the late 8th century and early 9th century, Japan’s Emperor Kammu sought to consolidate and expand his rule at the northern end of Honshu, the main island of Japan. Unfortunately for him, his army was undisciplined and lacked motivation; the tribes among the “barbarian” Emishi people, related to but not identical to the Ainu, that resisted Kammu were able to thoroughly beat back Kammu’s forces.

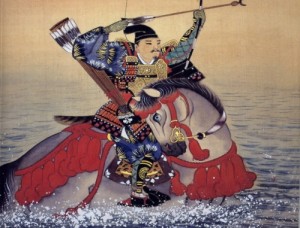

Emperor Kammu, being a stubborn man, would not settle for defeat. Kammu introduced the title of shogun (or in its full form, “seitai daishogun,” The Great General who Subdues Eastern Barbarians) and placed the holder of this rank in charge of an army drawn from the powerful regional clans. These soldiers were masters of a difficult method of combat: archery while mounted on horseback. Skill in riding and archery took a great deal of time and trouble, so these soldiers were either family of the rich and powerful themselves, or hired bows (as in, hired guns) who held loyalty to the one who paid the bills and put food on the table.

form, “seitai daishogun,” The Great General who Subdues Eastern Barbarians) and placed the holder of this rank in charge of an army drawn from the powerful regional clans. These soldiers were masters of a difficult method of combat: archery while mounted on horseback. Skill in riding and archery took a great deal of time and trouble, so these soldiers were either family of the rich and powerful themselves, or hired bows (as in, hired guns) who held loyalty to the one who paid the bills and put food on the table.

form, “seitai daishogun,” The Great General who Subdues Eastern Barbarians) and placed the holder of this rank in charge of an army drawn from the powerful regional clans. These soldiers were masters of a difficult method of combat: archery while mounted on horseback. Skill in riding and archery took a great deal of time and trouble, so these soldiers were either family of the rich and powerful themselves, or hired bows (as in, hired guns) who held loyalty to the one who paid the bills and put food on the table.

form, “seitai daishogun,” The Great General who Subdues Eastern Barbarians) and placed the holder of this rank in charge of an army drawn from the powerful regional clans. These soldiers were masters of a difficult method of combat: archery while mounted on horseback. Skill in riding and archery took a great deal of time and trouble, so these soldiers were either family of the rich and powerful themselves, or hired bows (as in, hired guns) who held loyalty to the one who paid the bills and put food on the table. With this army, Emperor Kammu was able to subjugate the so-called barbarians and expanded his rule, just as he had planned. Nonetheless, the Emperor now had his victory and a large army of low-born warriors under a single general, loyal not to him, but to a variety of clan leaders across Japan. Kammu did what many people would have done: he disbanded the army. Unfortunately for the emperors as a whole, this had the result of disbanding most of his worldly influence beyond the capital (Kyoto).

In time, the great clans themselves would seize control of the government from under the feet of the emperors, with the prime minister’s seat always belonging to someone well connected and powerful. With such political power, the clans were able to appoint magistrates (judges) of their own choosing, or of the clans themselves. Therefore, armed with both the power of the law and the power of the iron fist, these large clans were able to dominate the government and oppress lesser officials – the saburai – and the peasantry with complete impunity. It sounds like something out of “Zorro.”

Some saburai had their land stolen from them; others were fighting desperately to keep what little they had. Drawing on the lessons of the army that had subjugated the Emishi, the samurai themselves began training intensively in the bow and horse and banded together, wherever needed and wherever possible, to oppose the large clans’ encroachments. Others joined their ranks as warriors despite having no history as retainers of the Emperor. At any rate, that retainer status meant little; the Emperor was unwilling or unable to protect those at the bottom of the government pyramid from out-of-control magistrates.

By blood, and steel, the samurai carved out a place for themselves in the new Japan. In time, those who survived and thrived as warriors became seen by the great clans as highly desirable soldiers and bodyguards, not for the Emperor, or for Japan, but for themselves. The stakes were high; disloyalty could ruin a ruler even faster than incompetence. Thus, the samurai adapted their existing concept of service; from now on, they simply served feudal warlords and clan leaders instead. The core principle – faithful service – had not changed. The method had simply evolved from the pen to the sword (or rather, bow).

As the armed samurai became a fixture of private service, they once again became an important part of the government itself. (After all, the support of a large clan meant political patronage as well.) However, the Chinese-style bureaucrats who filled the middle ranks of the government, as well as the representatives of the great clans who ran the government, regarded these samurai as barely better than barbarians themselves.

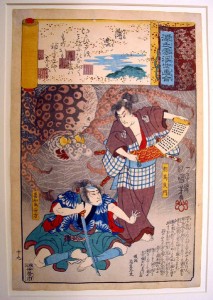

Fighting for respectability, the samurai turned once more to the pen, developing the concept that the samurai must be a master of pen and sword, not just one or the other. In this way, the samurai showed he was not just a warrior, but a civilized man with a proper place in government.

Fighting for respectability, the samurai turned once more to the pen, developing the concept that the samurai must be a master of pen and sword, not just one or the other. In this way, the samurai showed he was not just a warrior, but a civilized man with a proper place in government. The power of the emperors waned, and soon, the samurai were instrumental in the civil wars that would wrack the country, ebbing and flowing until the “Warring States Period,” or “sengoku jidai,” finally ending in the “Edo period” that resulted centralization and a long relative peace. Thus did the samurai return to their original role as government retainers, albeit still to individual lords rather than to the Emperor. Finally, the Meiji Restoration abolished the samurai, replacing the entire concept with civil service loyal to the Emperor himself, thus “restoring” the ancient system.

Of course, a lot happened in between… but that is another story.

Thank you for reading!